The Malham Dig

The

pages below are under development and will be updated on a regular basis.

All images are from the author's collection unless otherwise stated.

Click on image for larger view, back space to return.

The "Malham Dig", "The Craven Dig", or "Waterfall's Folly", as some cynics called it, was arguably the greatest potholing dig in the Dales, certainly of the late 1940s and early 1950s.

A large stream sink, an equally large resurgence, and some 400 feet of unbroken limestone were the ingredients for a scheme to unveil a vast cave system hidden behind the stony facade of Malham Cove.

It was no folly, in fact it was a carefully conceived project engineered by Arnold Waterfall and Dennis Brindle. Enthusiastically taken up by other members of the Craven Pothole Club, the project was abandoned in 1952 when at a depth of some 90 feet the quantity and nature of the fill was found to be quite overwhelming.

"Left: A large stream sink" - takes the waters from Malham Tarn: this is the location of 'The Malham Dig" of 1952. December 22, 2015.

"Right: 400 feet of unbroken limestone." - Malham Cove in summer.

June 14 2009.

Left: Tarn Sink in normal conditions, this is the point nearest the Tarn at which the water sinks. In times of flood the stream travels a further 360m to sink at the location of "The Malham Dig": see above left and adjacent picture.

March 27, 2016.

Right: The true location of "The Malham Dig" is defined by the large rocky scar on the hill, upper part of the picture, seen in 1952 Picture 9 in the mono series lower down.

March 27 2016.

Left: In high water levels the main flow of water from the tarn sinks partly to the west of this wall but the majority flows through the wall to sink in a pronounced hollow at the east side of the wall.

January 1, 2005.

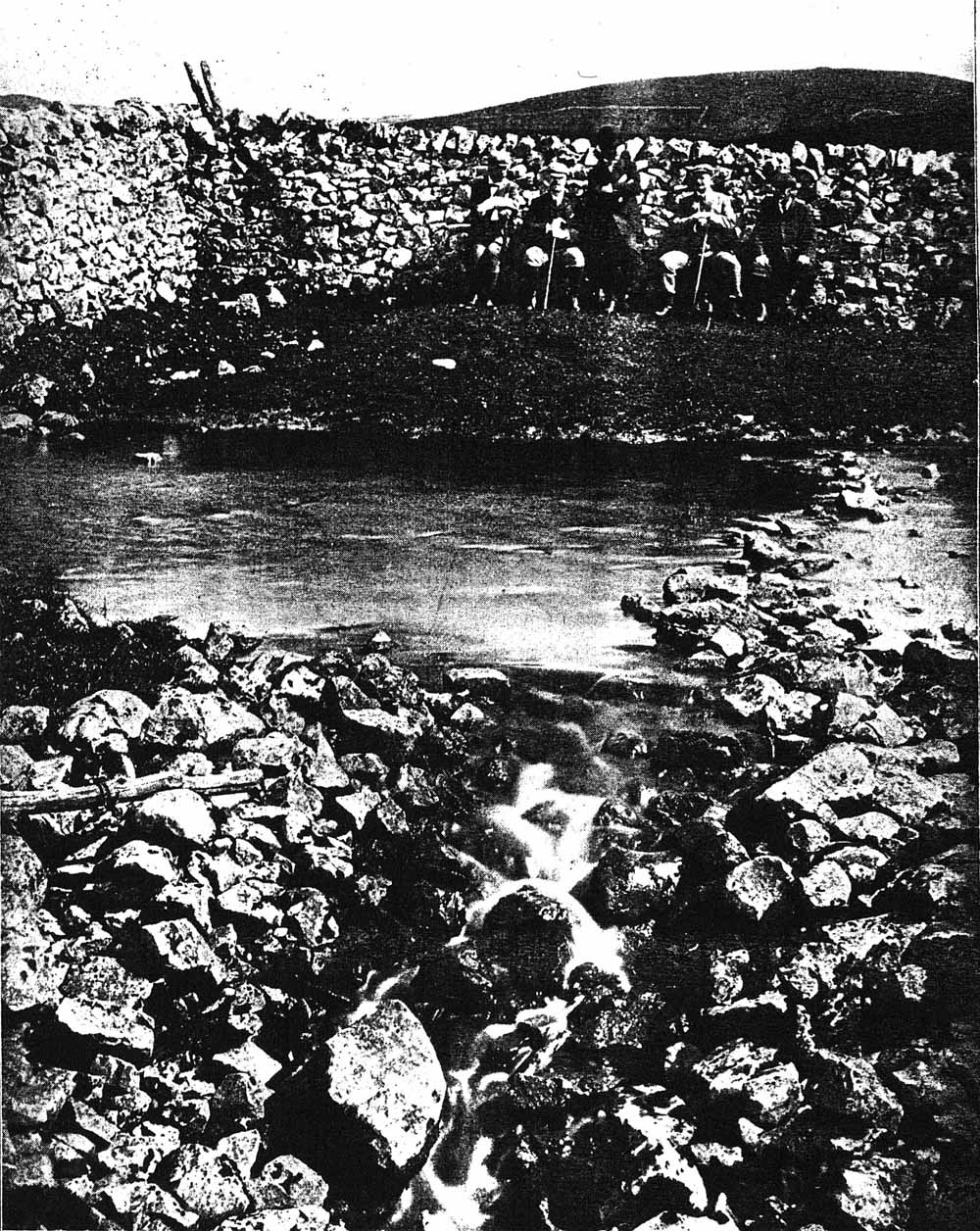

Right: This image, by Geoffrey Bingley of Leeds, is from Howarth 1900 (opposite page 25, see References below) shows the same location from the east side of the wall. A goodly flow of water is sinking in this rocky basin.

c 1899.

Left: The main rising at Malham Cove.

August 8, 2007.

Right: The divers' entry protected by a grid for safety of the public.

June 17, 2015

View from Chapel Fell looking over Tarn Moss and Malham Tarn towards Great Close Hill.

March 10, 2016

The

Tarn outlet and sluice, Great Close Hill in the background.

March 10, 2016

Smelt Mill Beck and the old smelt mill chimney.

March 10, 2016

Smelt Mill Sink.

March 10, 2016

The catchment for Smelt Mill Beck.

March 10, 2016

Aire Heads where one of the two spring sources meet up with Malham Beck, on the right, to form the true River Aire. The springs are close to the tree right of centre.

March 10, 2016

Aire Heads, the real source of the River AIre, according to some, where the waters just arise out of the ground from two sources close together: this is the larger spring.

April 21, 2016

Waterhouses Rising, one of several feeders to the Tarn

Arnold Waterfall

In early 1990 I called on Arnold Waterfall at his Draughton home with a Club newsletter, as I had done many times before. He was ill in bed: "something was eating away at his inside", he told me, but, as ever, he was keen to hear the latest caving news and to learn who was doing what. He gave me a box of papers, maps and photographs and asked me to look after them as they might be useful some day. He was well aware that we were unlikely to meet again.

It was Arnold's wife Phyllis who told me that Arnold and Dennis Brindle were master-minds behind the great "Malham Dig": it was their brainchild, they started it and they enthused many others.

Arnold had done his homework and, in the 1949 CPC Journal, he outlined the history

of studies in this most fascinating of speleological challenges. This covered pioneering work by the Yorkshire Geological and Polytechnic Society who organised dye tests from various sinks high on the moor to the two principal known risings at Malham Cove and at Aire Head Springs.

The great "Malham DIg" was started in 1949 and that story is told a little further down. When the excercise came to an end it was Arnold who made sure that everything was left in order.

In 1954 the hole had been covered over for some time but there was a problem with passers-by throwing wallstones down between the boards. When Arnold learnt that a local farmer had an powerful earth mover nearby, he hired it for the day, for £5, and had the hole completely filled in and landscaped. On the following Saturday, late July 1954 I think, when I called in at Arnold's shop in Skipton, he asked me to join him as he went up to Malham to make sure the job had been done properly.

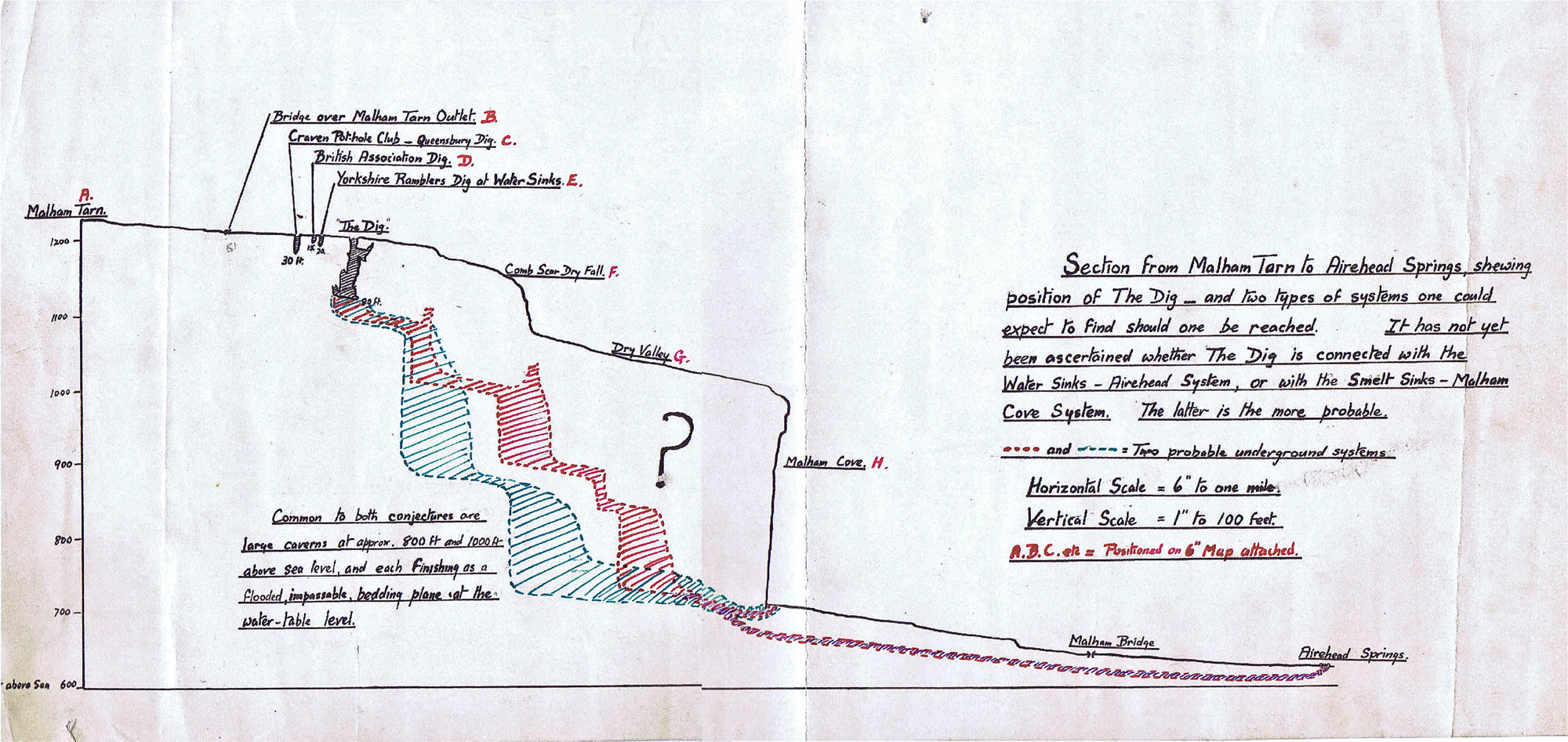

The sketch below created by Arnold illustrates the ideas (dreams) in mind at the time.

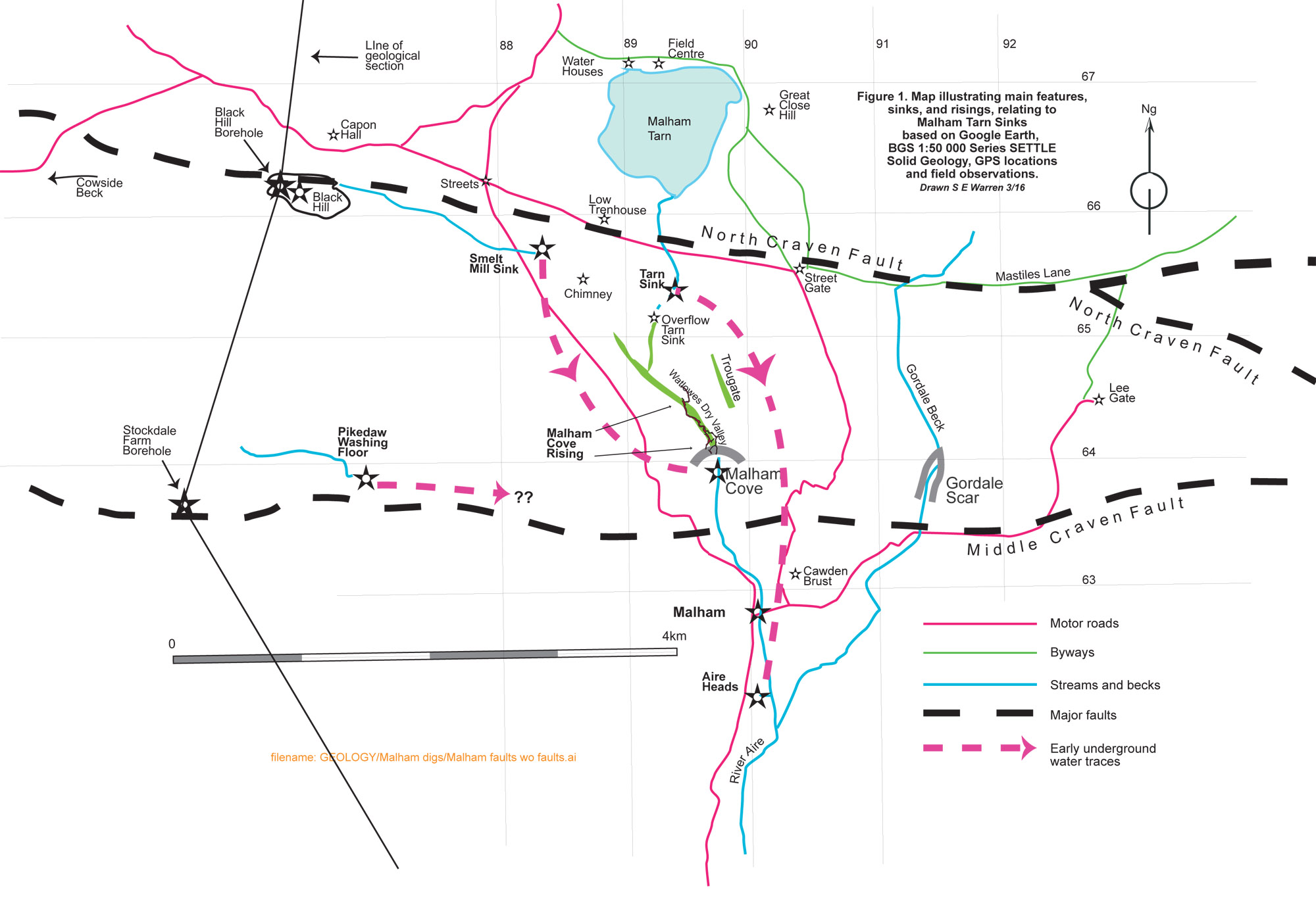

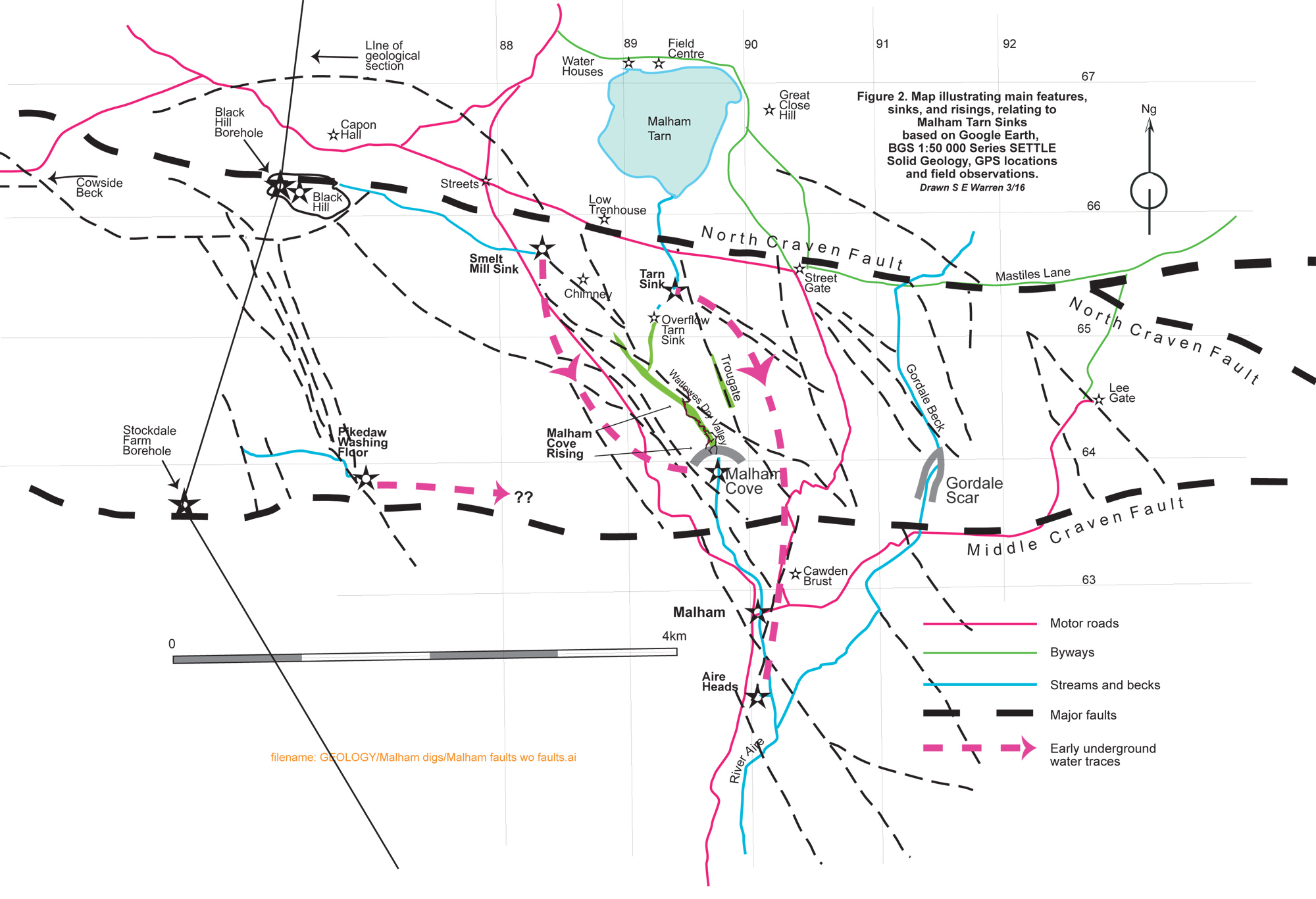

The study area

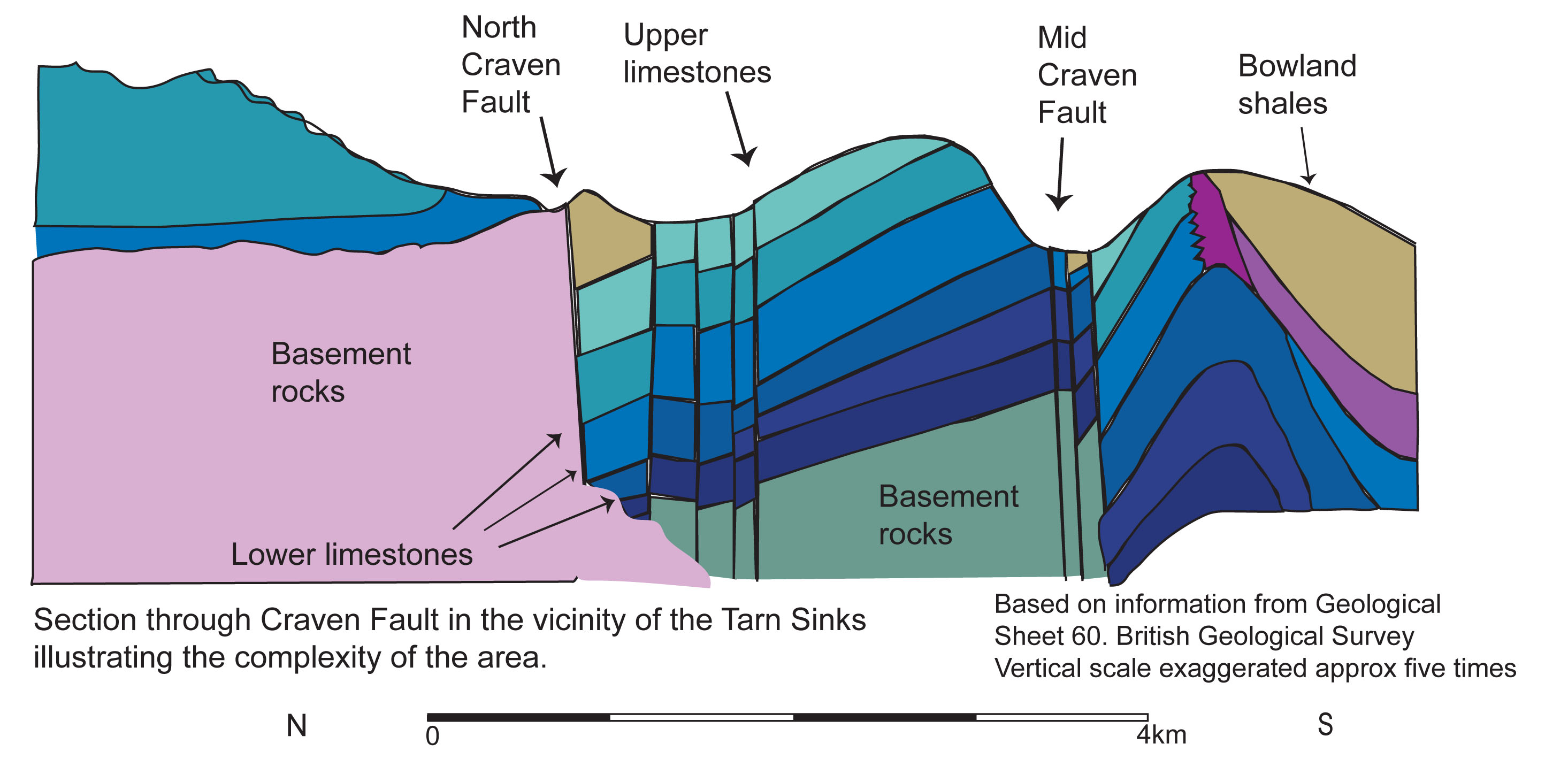

The sketch map below, Fig. 1, shows the disposition of the various relevant features. In this predominantly limestone country, Malham Tarn lies on an impermeable bed of Silurian basement rock due to the the presence of the Craven faults just a little way to the south. The North Craven Fault passes some 200m to the south of the Tarn and displaces the strata some150-200m down to the south. Less than 2km to the south of that feature the Middle Craven Fault has resulted in a further displacement to the south of another 200m or so. However the vertical displacement varies considerably along the course of these geological upheavals. The net result is a thickness of some 200m of limestone, with that relevant to the study of the Tarn Sinks approximating to some 130m, or 400ft as mentioned in the introduction.

The nature of the geology in this area is not at all simple. Along the zone between the North Craven Fault and the Middle Craven Fault there are numerous subsidiary fracture lines generally disposed in a SE-NW orientation: this arrangement is shown in Figure 2.

In the introduction to his paper of 1900 (see below) Howarth very succinctly summarises the geology of the immediate area, as follows:

From the valley of the Ribble by Stainforth, Neals Ing, Capon Hall, and Malham Tarn runs a long strip of Upper Silurian rocks which die out under the Carboniferous Limestone just eastwards of Upper Gordale where the beck leaves the moor and takes to the gorge.

This strip is brought up by the North Craven Fault, and its southern edge is sharply marked by the line of fault and may be easily traced the whole distance. On the north this strip is bounded by the overlying Carboniferous Limestone, which has been very unevenly denuded and presents a long sinuous front to the Silurian, here rising into sharp escarpments as at Great Close and behind Malham Tarn House, and there receding in long gentle slopes as on Chapel Fell, Knowe Fell, and about West Side House.

In a line across by Neals Ing and Cattrigg the Silurian is nearly two miles wide, half a mile west, of Capon Hall if narrows to zero, widens to about a. mile at Malham Tarn, and narrows again to where it disappears eastwards near Gordale Beck.

The area under consideration is included in a line drawn from near Capon Hall on the west, Knowe Fell on the southerly side of Fountains Fell on the north, round by Middle, House and East Great Close (under Hard Flask) to High Stoney Bank on the east, and Kirkby Malham in the Aire Valley on the south. This area forms the upper watershed of the River Aire.

What happens is this. All the rainfall on the limestone on the north side of the Silurian, and several springs which rise up the slopes of Knowe Fell towards Gentleman's Gate and Fountains Fell, sink info the limestone and are brought to the surface again at the edge of the Silurian rocks which are tilted at a high angle. These waters flow across the Silurian rocks, either in streams or through Malham Tarn, only to sink again on reaching the limestone on the south side.

To this rule Gordale Beck has been regarded hitherto as the only exception, but it now transpires that Gordale stream is only partially an exception, and is itself undergoing absorption into the limestone. These waters, sinking south of the North Craven Fault, reappear below the great escarpments about Malham and Gordale formed by the Mid Craven Fault, with all the rainfall and springs on the limestone area lying between the two lines of fault. The limestone on the south side of the Silurian absorbs all surface waters just as if does on the north side.

The geological section below, marked on the above sketch map as 'Line of Section', more graphically illustrates the complexity of the ground around the Craven faults highlighting the strata relevant to the Tarn Sinks conundrum.

The images below illustrate how the strata is affected by these geological upheavals.

Indisputably, the challenge remains as to how the movement of underground waters in this area may be explained.

Left: vertical strata on the west side of a normally dry gorge at the entry of Tarn SInks Valley to Watlowes dry valley near Comb Hill. March 27, 2016 (12a)

Similarly, on the opposite side of the gorge to above.

March 27, 2016 (13a)

A few metres higher up, a significant fracture zone is seen to the right of centre in this scene.

March 27, 2016 (15a)

A significant crush zone is seen in the central area of this scene.

March 27, 2016 (17a)

The south-west facing side of Comb Hill is well exposed here showing undistorted strata. October 25, 2015 (08)

The normally dry valley from the Tarn Water Sinks down to Watlowes Dry Valley ends quite dramatically at the Dry Fall. This is an interesting free climb for the adventurous.When water levels are exceptionally high the tarn waters reach this point and have been known sink in a pool at the foot of the fall

April 21, 2016

Earlier work

Lord Ribblesdale of Tarn House and subsequently William Morrison had shown great interest in the the phenomenon of the disappearing Tarn waters, as had the noted Malham schoolteacher Thomas Hurtley (1768) and others. Furthermore, an earlier member of the Yorkshire Geological and Polytechnic Society

had also spent some time attempting to unravel the peculiarities of the sources of the River Aire. (Tate T, 1879 and 1895).

It was not until the pioneering work of 1899 by co-operation between the British Association and the Yorkshire Geological and Polytechnic Society (Howarth J H, 1900) that reliable conclusions were established.

1) that flood water at the Tarn Sinks reached Airehead Springs in 90 minutes, and:

2) flood water at Streets Smelt Mill Sinks took 130 minutes to reach the rising at the foot of Malham Cove.

There were other options one of which concerned the possible resurgence for water sinking at the Calamine Mine washing floor on Pikedaw 2km to the south-west.

They found also that:

1. locals knew the difference between the darker coloured water resurging from the Cove and clear 'petrifying' water at Aire Heads.

2. water from the Cove constantly discoloured due to pollution from Streets Smelt Mills, or from the mines on Pikedaw.

In previous years several attempts had been made to solve the mystery of the underground water courses. In 1890 Professor Sylvanus Thompson had introduced 1 1/4 pounds uranin into one of Tarn SInks Whilst the BA and YGPS were working on the issue they tried out several tests varying from introducing salt, flood pulses, alcoholic solution of fluorescein, ammonium sulphate, fluorescein in 10 % aqueous potassium carbonate, one ton of salt in Smelt Mill SInk, 7 cwt ammonium sulphate into Upper Gordale Beck, 18cwt salt into "burst "on side of Cawden etc etc.

Resulting from all this two digs were undertaken at Tarn Sinks, one by the British Association that ended at a depth of 12 feet, and one by the Yorkshire Ramblers Club that went down to 18 feet. (Several members of the Yorkshire Ramblers had previously been associated with the two above mentioned bodies).

The Malham Dig

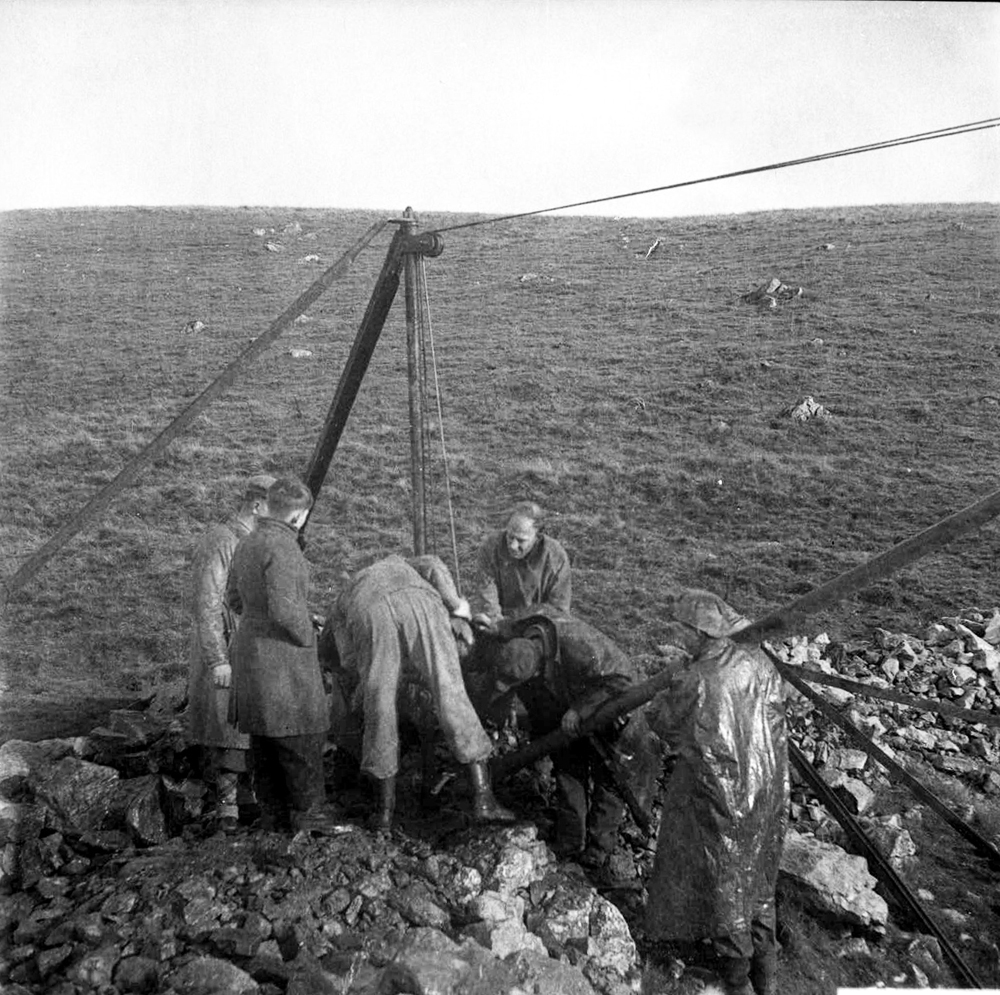

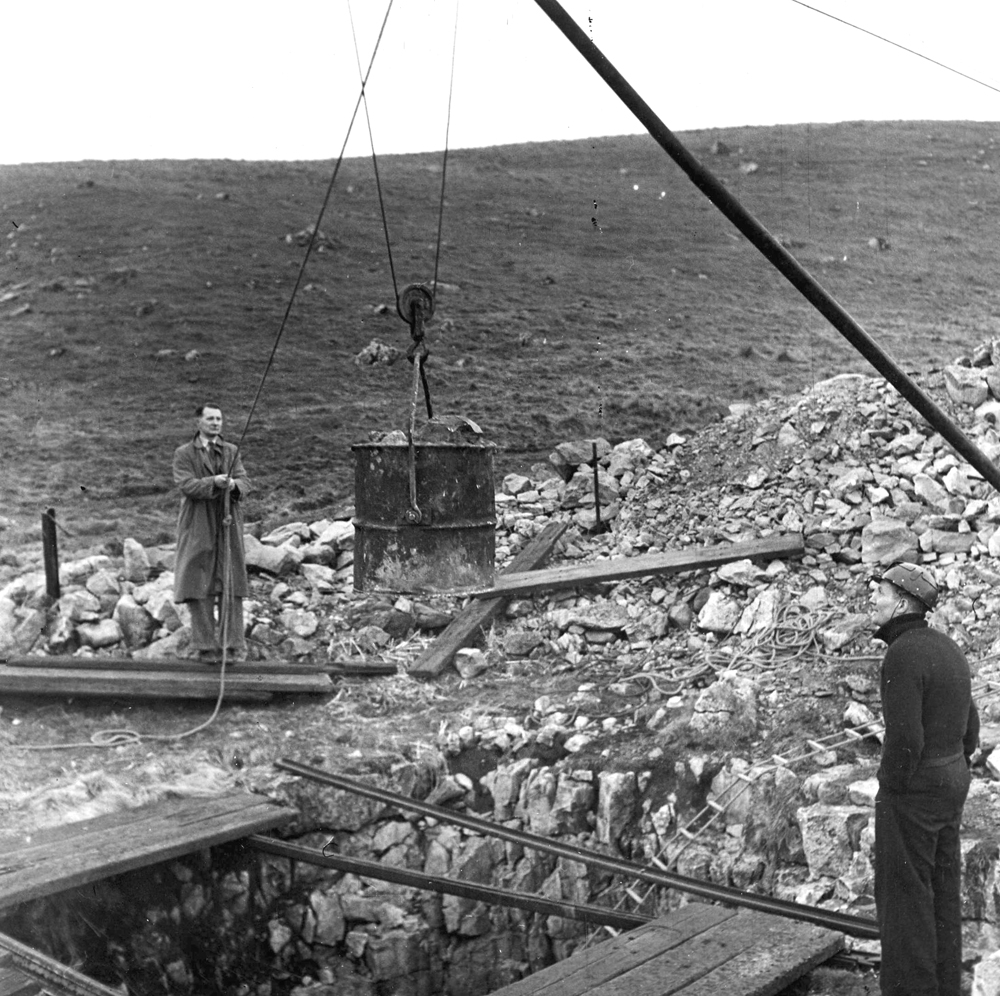

Summarising Arnold Waterfall's Journal reports, we learn that in 1946 the 'Queensbury Lads', (the Spencer brothers Bill and James, together with Eric Light), started digging down to attain a depth of 27 feet before abandoning the dig. Late in 1948, Dennis Brindle, Bill Farrow, Brian Hartley and and Arnold Waterfall started again, but some distance further down the Tarn Sinks valley, at the point that takes water only in flood conditions. "Turf was removed and the edge of a filled-in pothole was exposed'. 15 feet down some very large boulders, far too large to handle... some jelly was applied. At 20 foot level a hole went on the east side, "the passage floor, boulder-strewn (each boulder being white with deposit) descended steeply"… ended at a 20 foot aven. A three leg derrick crane was erected (on loan from Mr Longbottom's yard at Gragrave), and an old winch was given by a local farmer... material in layers of packed sand, and gravel, easy rubble, large boulders, the order being repeated many times... amongst the boulders were many waterworn rocks which must have been trundled down by a much larger stream. At 40 feet a small hole was uncovered under west wall, strong draught, which blew up through the floor, about this time a large mass of tufa was unearthed and had be be broken up into small pieces each weighing over 2cwt, floor level at this time. 50 feet from the surface.

From Arnold's CPCJ 1952 account:

Hard work, rapid progress, shaft began to widen, "at 60 feet down, one day whilst I was working alone I heard a stone roll at the Tarn end and, with a crowbar I made a hole large enough to get through. Squeezing between boulders I slipped down into a small chamber where I was able to sit up and look around...

... a solid wall 10 feet away and a crawl led round to the Cove end of the chamber.

To lower the shaft by 12 inches would mean 8 times as much work".

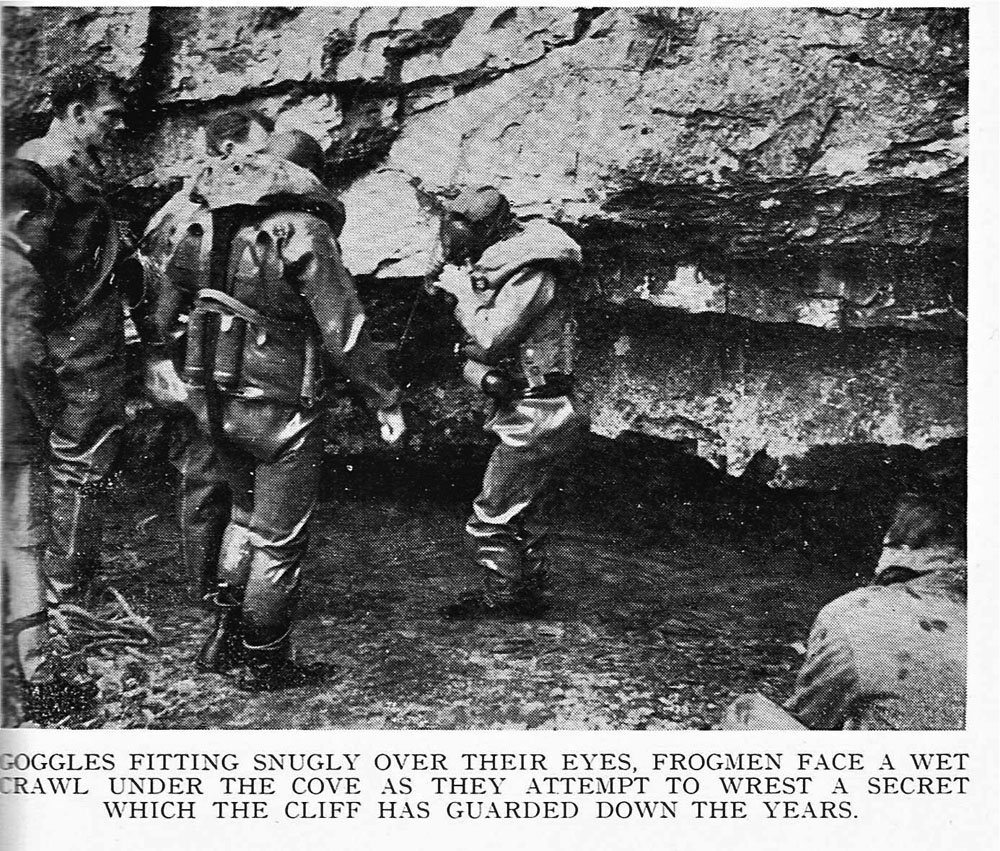

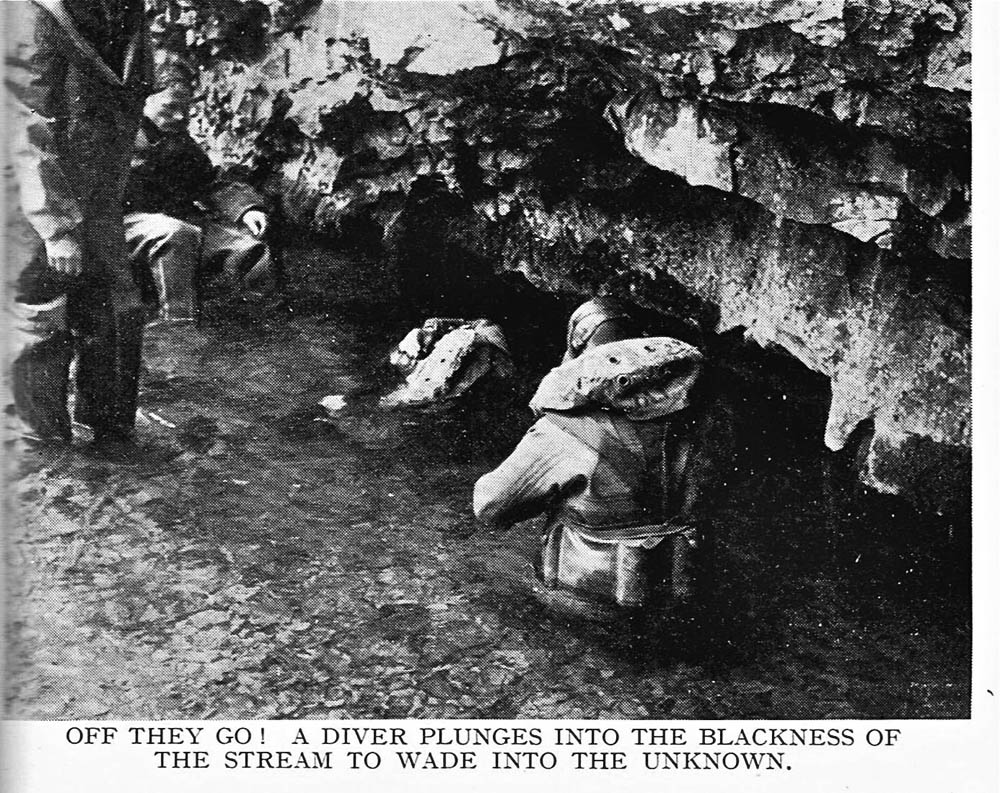

At the beginning of this year (1952) GG equipment moved to the shaft, - no more hand winding... a previous loan of winch from Stoke-0n-Trent Pothole Club proved power was insufficient for our needs. At height of endeavour bringing out 6 tons per day - making little impression - ran into trouble once more, western wall consisted of rubble and at 10 feet high began to fall which meant more debris to move. Some very big floods swept down the hole but no sign of backing up of waters. still chance of a breakthrough. Now in series comparable to base of Comb Scar. Around this time: 'attempt to dive Malham Cove in frogmens' suits, stream bed lowered and got under rock arch". CPCJ 1953: inset photos show " When the frogmen came to Malham Cove" A Butcher. Derbyshire Section of Cave Diving Group, May 1953, after 70 feet became to low"

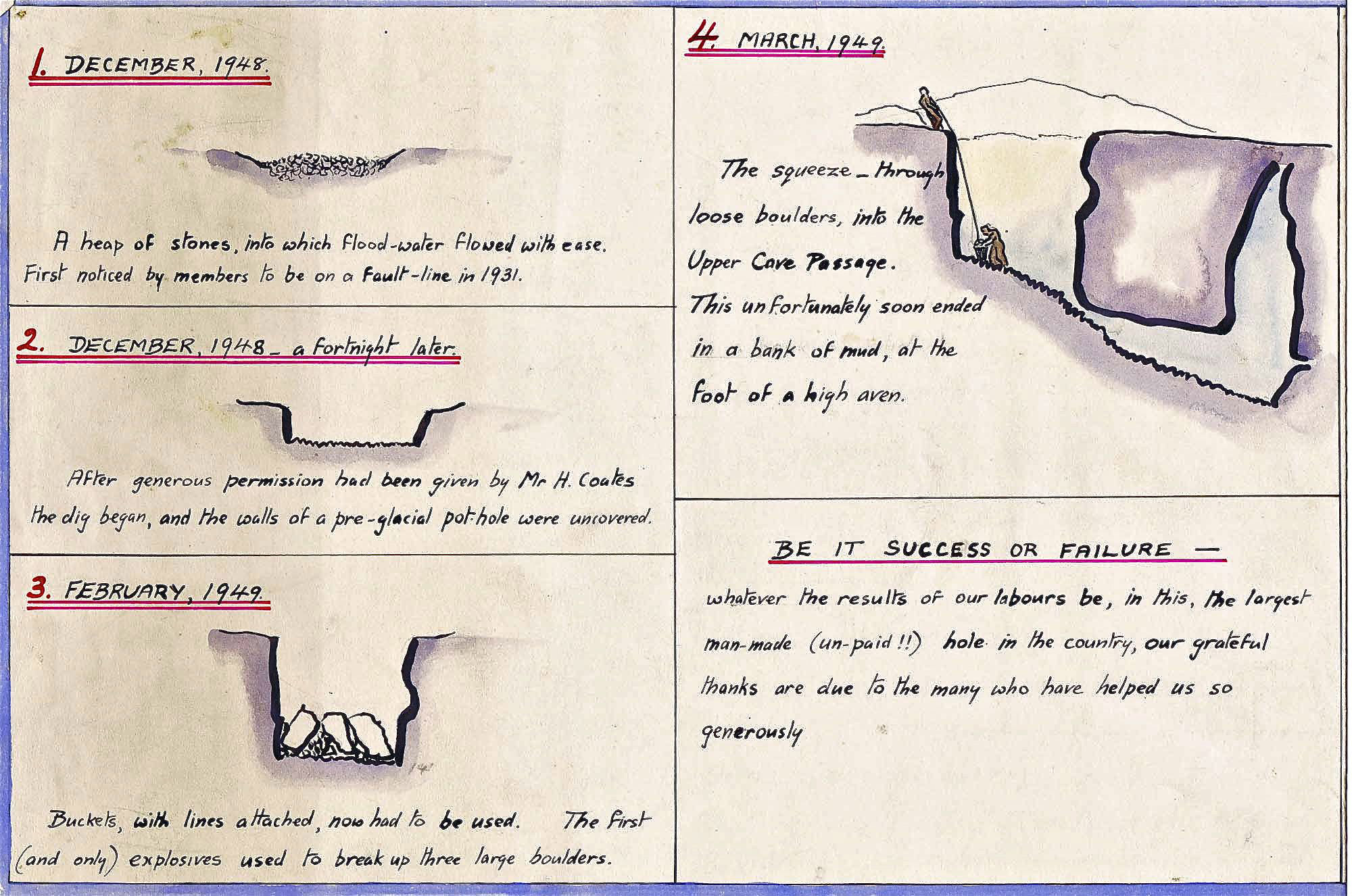

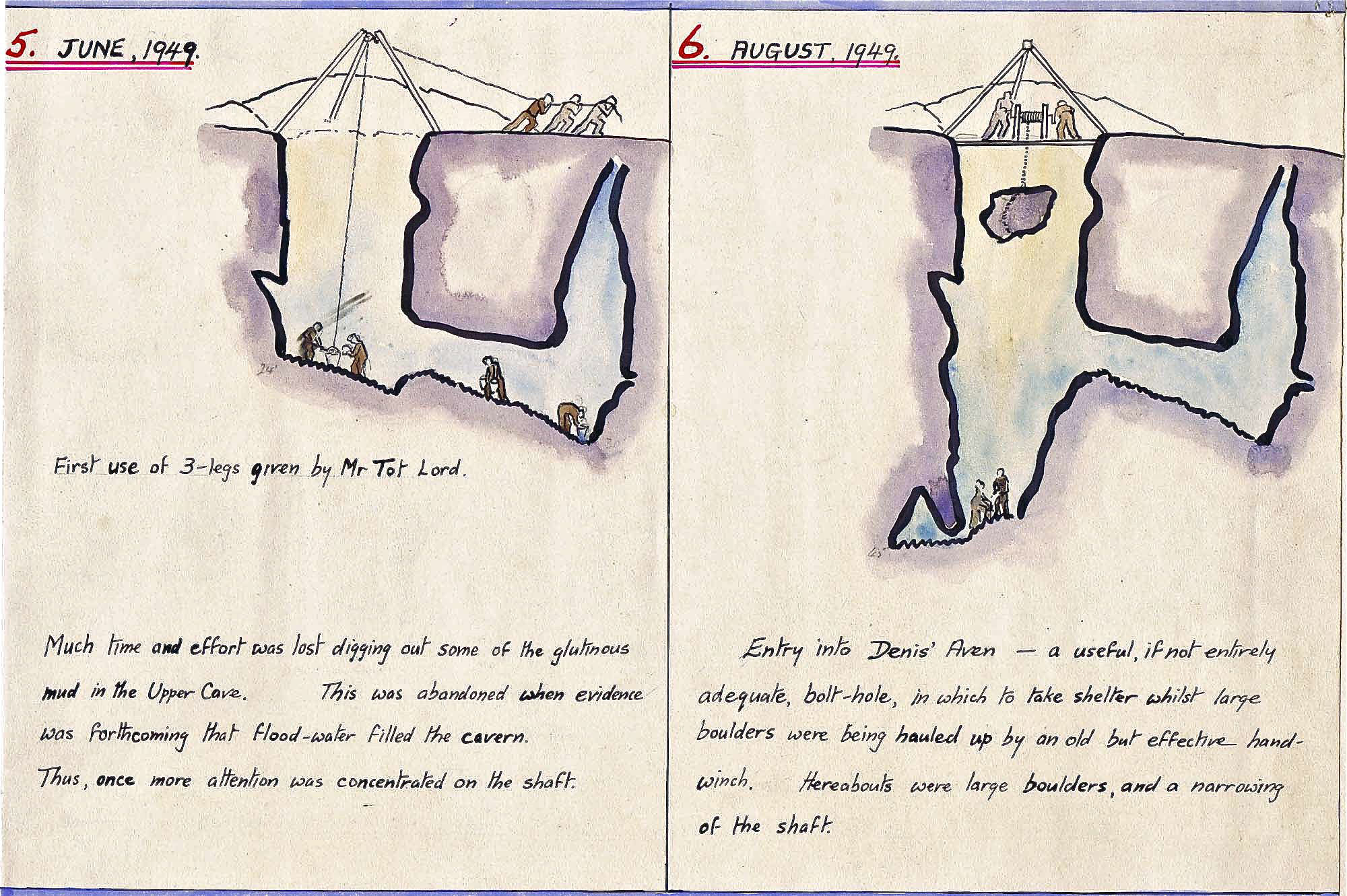

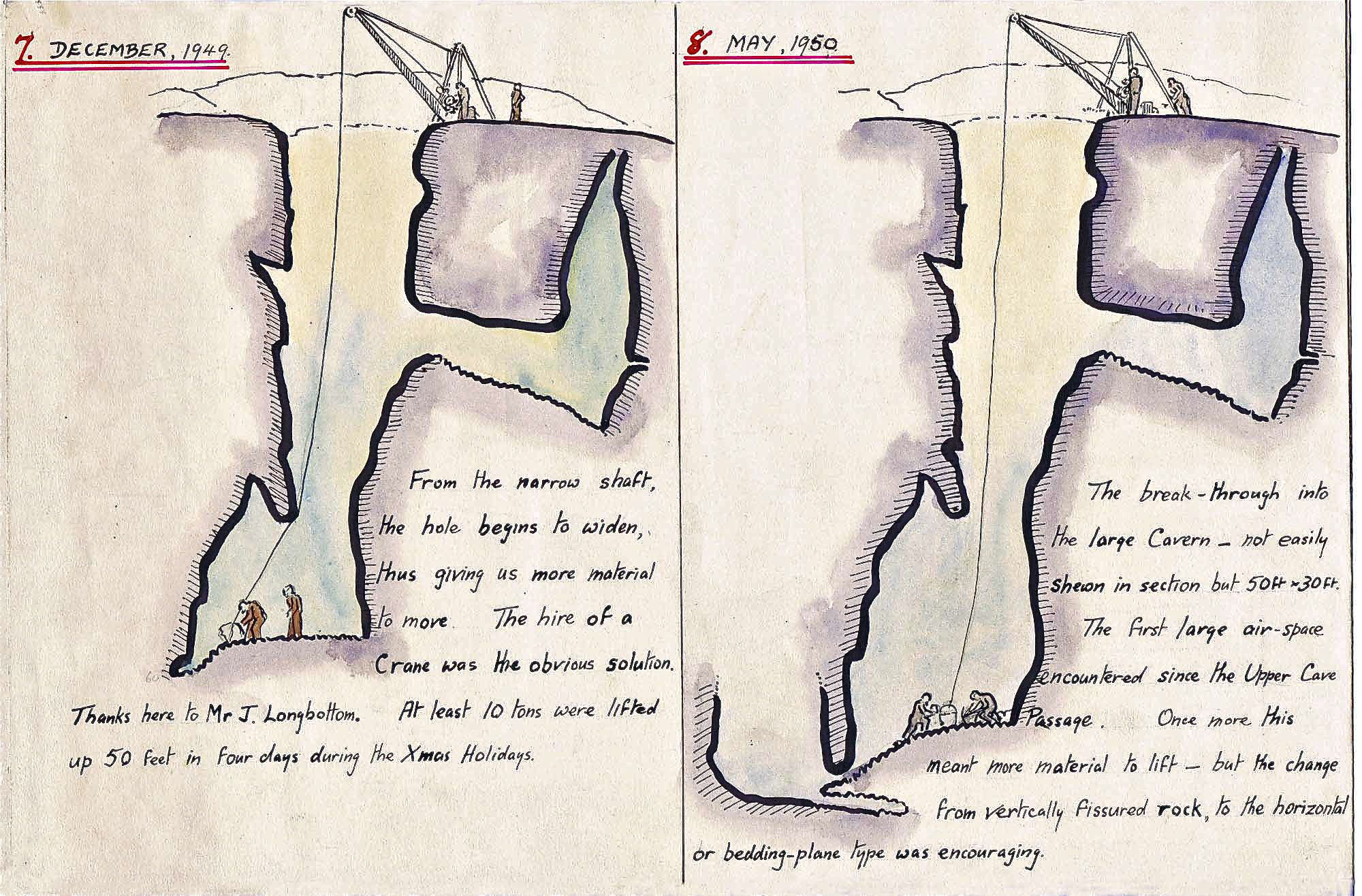

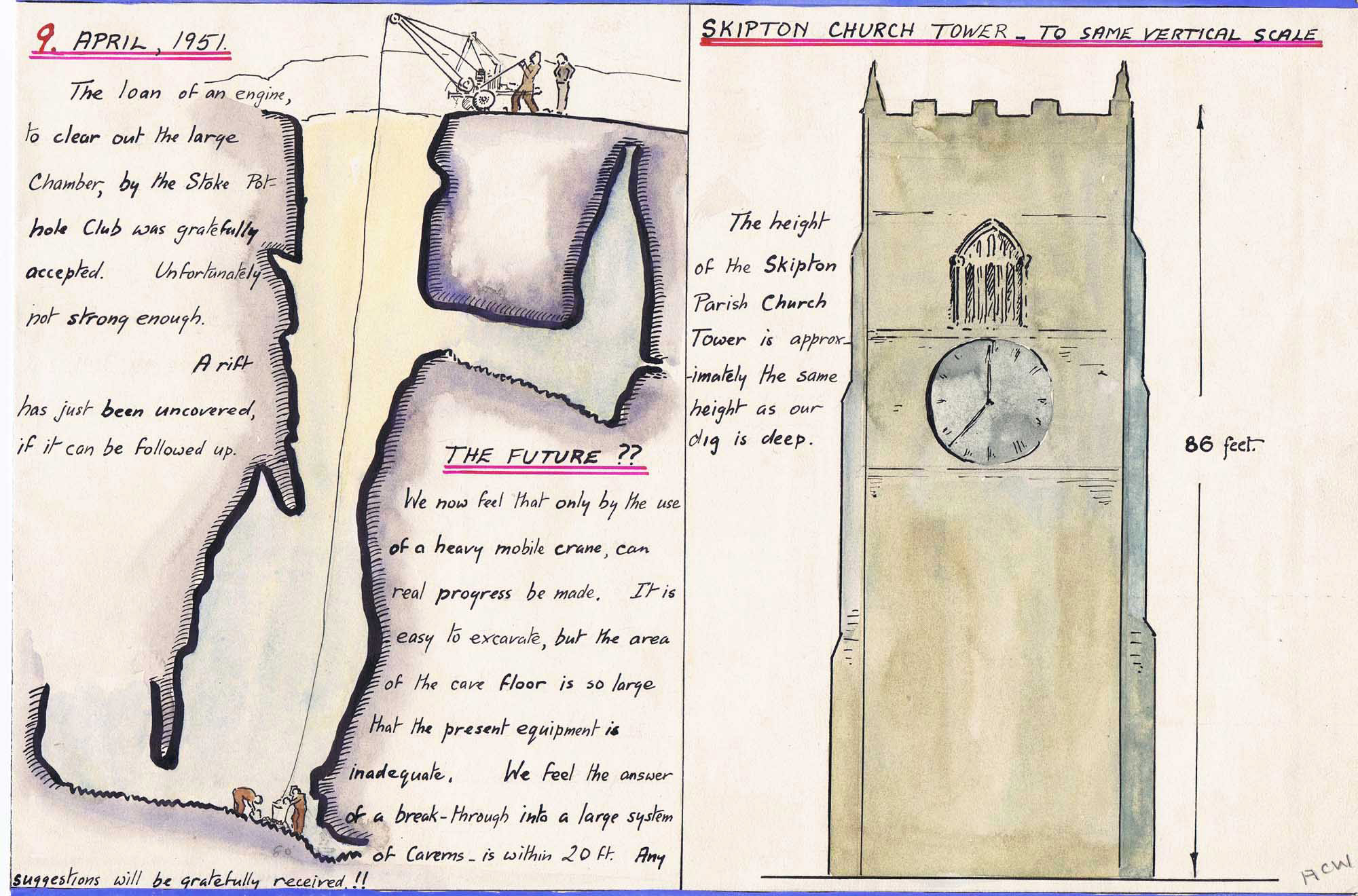

Arnold Waterfall was a concientious and orderly recorder in all his affairs, not least the workings of the Malham Dig. The sketches below show a record of the dig from early beginnings to the state of affairs in April 1951 although activities did continue into later in the year.

The Albert Mitchell archives

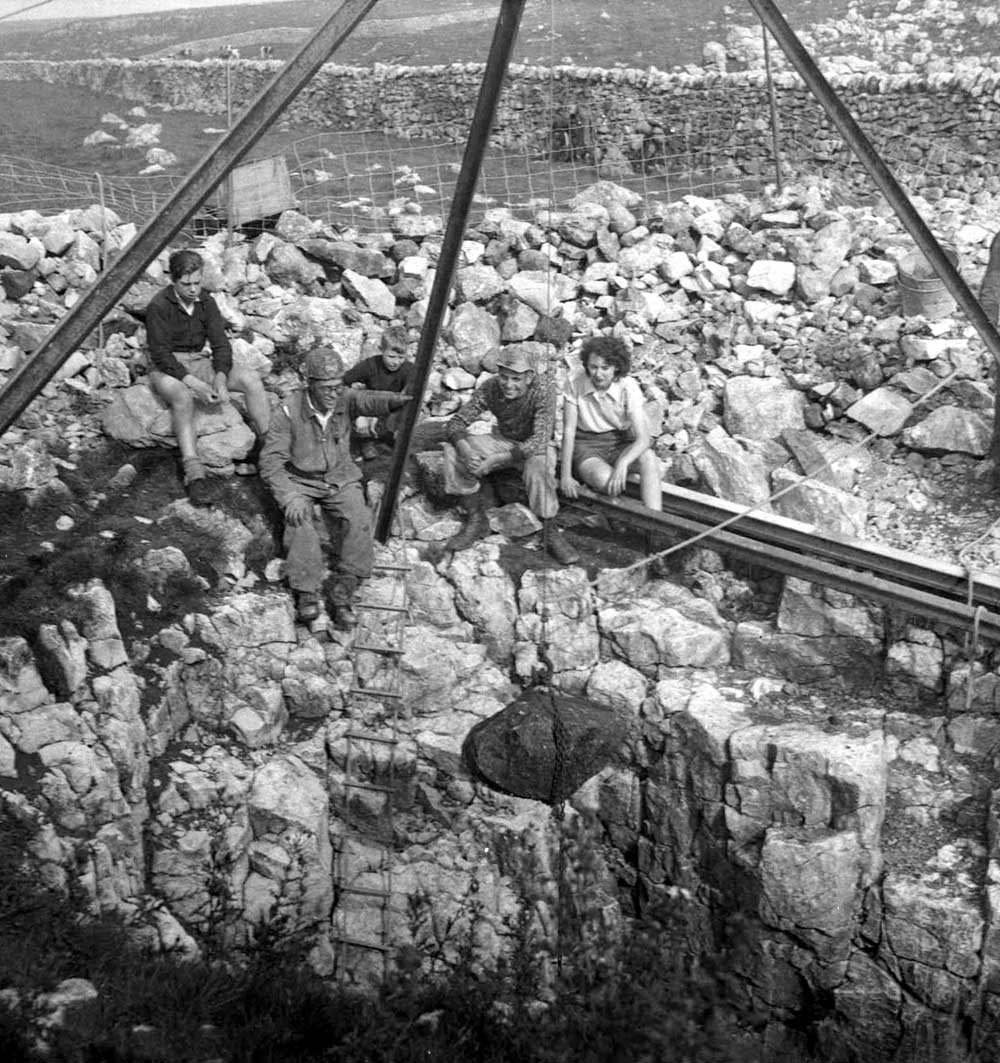

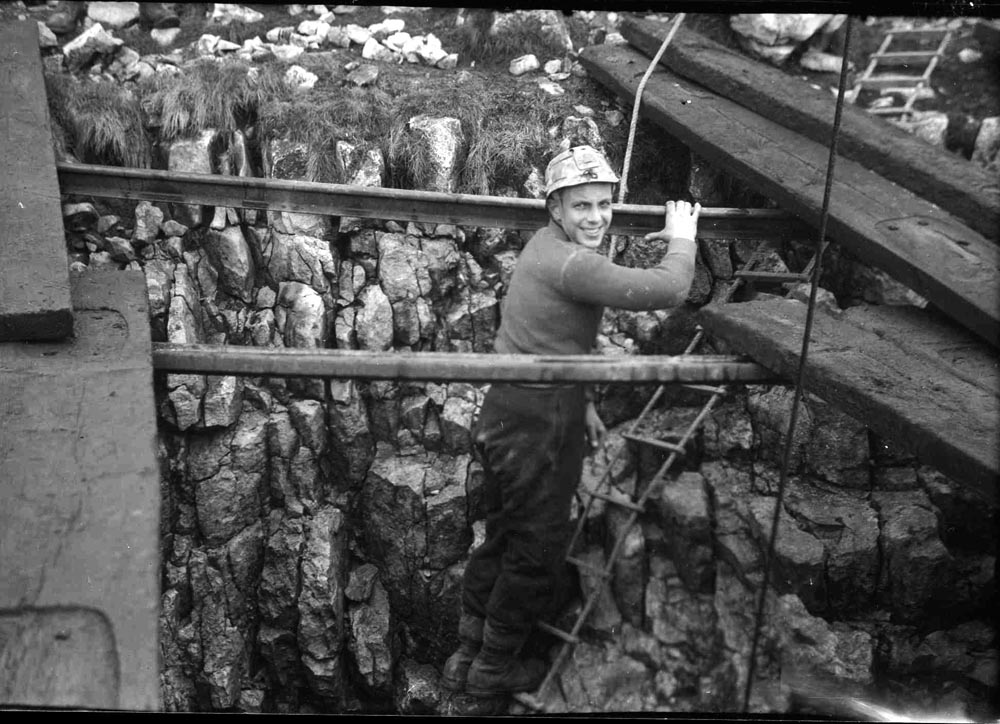

The photographs below were amongst many monochrome glass slides found amongst Arnold Waterfall's collection and in another collection of monochrome film negatives passed to the author by Albert Mitchell's widow, Doris.

These images tell their own story but some have details given to the author by Edgar Smith. It is probable that all these photographs were taken by Albert Mitchell.

1. The earliest days.

2. A little further on but still hauling spoil out with a rope and bucket, sat on a plank.

3. Still digging through the winter.

4. Now with a three legs and pulley.

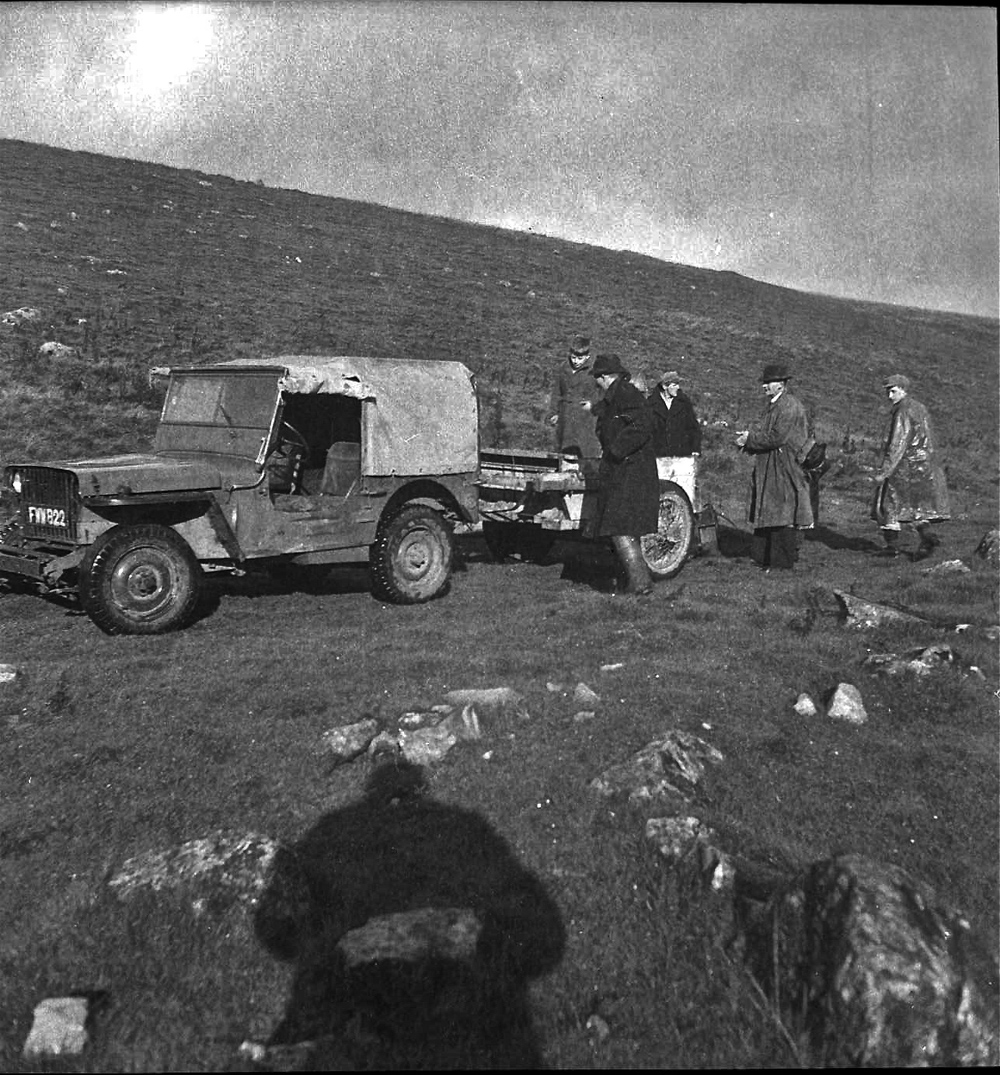

5. Jeep rolls up possibly with GG winch on board.

6. The spoil heap gets bigger, note just visible is the hand operated winch on a frame.

7. All hands to the winch.

8. Some large chunks of rock came out, Norman Brindle centre picture.

9. Rhodes Thompson to the right wearing a beret.

10. Unknown figure on the rope ladder

11. Dennis Brindle correctly tying two rope ladders together, reef knot with two half hitches each side. Note bicycles against the wall. It was not uncommon for the Brindles to cycle up to the dig from Nelson.

12. Down in the bottom of the dig, looks like Arthur Hardy, Arnold Waterfall and Dennis Brindle sorting out a tangle of ladder - a frequent event in those days.

13. Untangling the ladder at the surface.

14. Lifelining

15. The builders crane from Gargrave has now come into operation

16. The scale of operations can be seen here.

17. Tom Jones on the winch, Bill Bowler in the bucket. Bill Bowler came to fame as the last man out of Gaping Gill before meets were suspended at the outbreak of WW2.

18. This shows quite clearly the operation of the builder's crane, and also trouble with the winch.

19. & 20. More trouble with the winch from two viewpoints.

21. Arnold Waterfall left, and Albert Smith right watch the last bucket to come out of the dig: end of operations.

In 1953 members of BSA instigated a series of 16mm films under the direction of Eli SImpson (see References 11). This clip from the series shows the Malham Dig site after operations had ceased and before the site was cleared in July 1954.

Thanks to John Cordingley for this information.

The Divers

"When the Frogmen came to Malham Cove" was the title of an article in the Craven Pothole Club Journal for 1953 wherein Arthur Butcher described an attempt to penetrate the Cove waters by the Derbyshire Section of the Cave Diving Group. CPC members spent some time clearing out boulders from the rising in preparation for the attempt.

The editor of the 1954 Yorkshire Ramblers Club Journal summed it up admirably:

In May 1953

"Sufficient boulders were removed by the Craven Potholers to enable two unnamed Cave Diving Group men to crawl below a cave six feet under water and walk. A cave stretched left and right but at 70 feet ahead the roof become too low for crawling".

The same writer famously summed up the Craven efforts as having "given much negative information to science".

On this occasion a couple of CPC members had a go at trying their hands at this cave diving idea. Just how far they got has not yet been recorded, (pictures below).

Photographs by Arthur Butcher

Left: Discussion time with Arthur Smith centre figure.

John Normington (left) and Hector Dickens (right) have a go in the 'Frogmen' suits.

More recent work

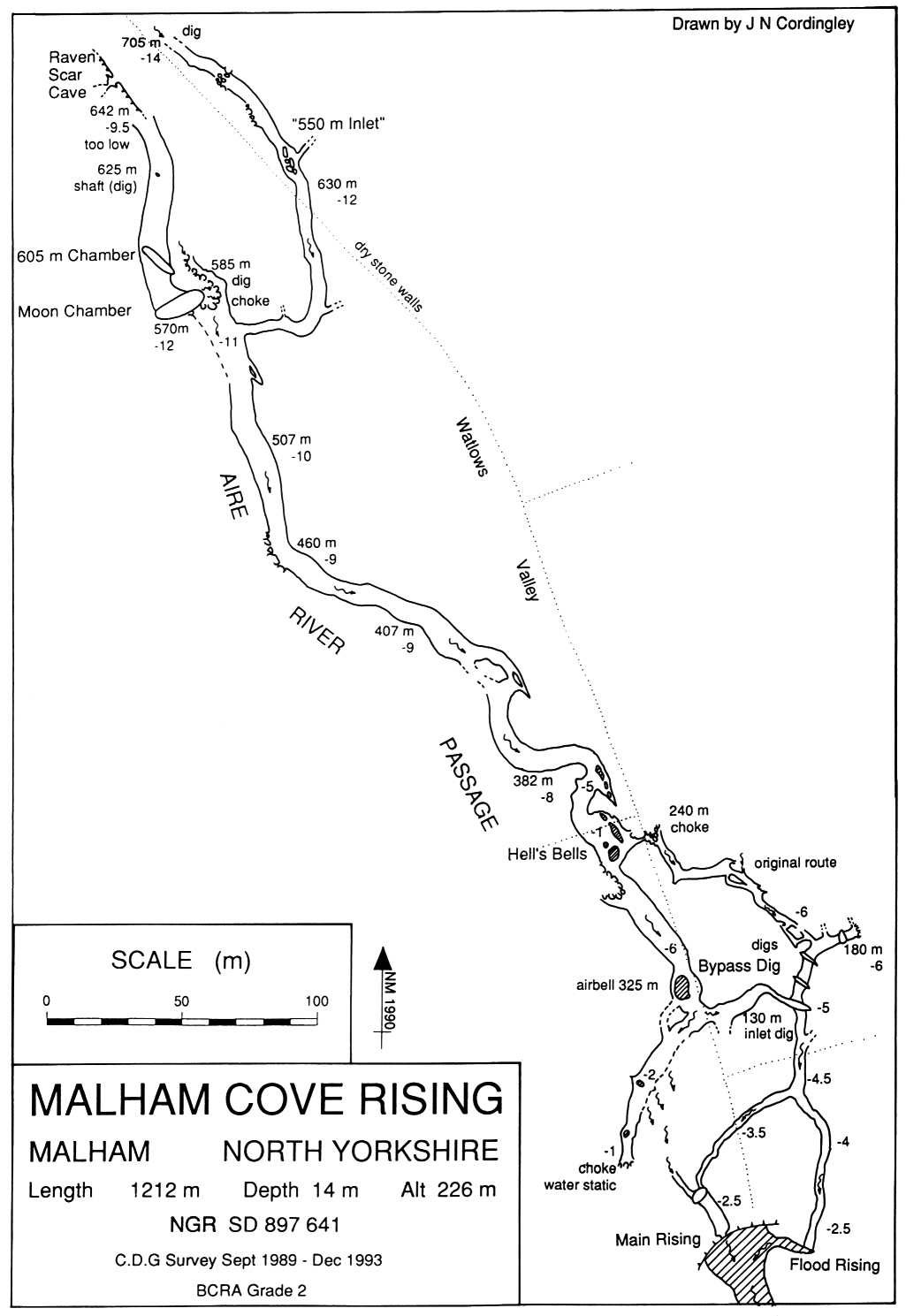

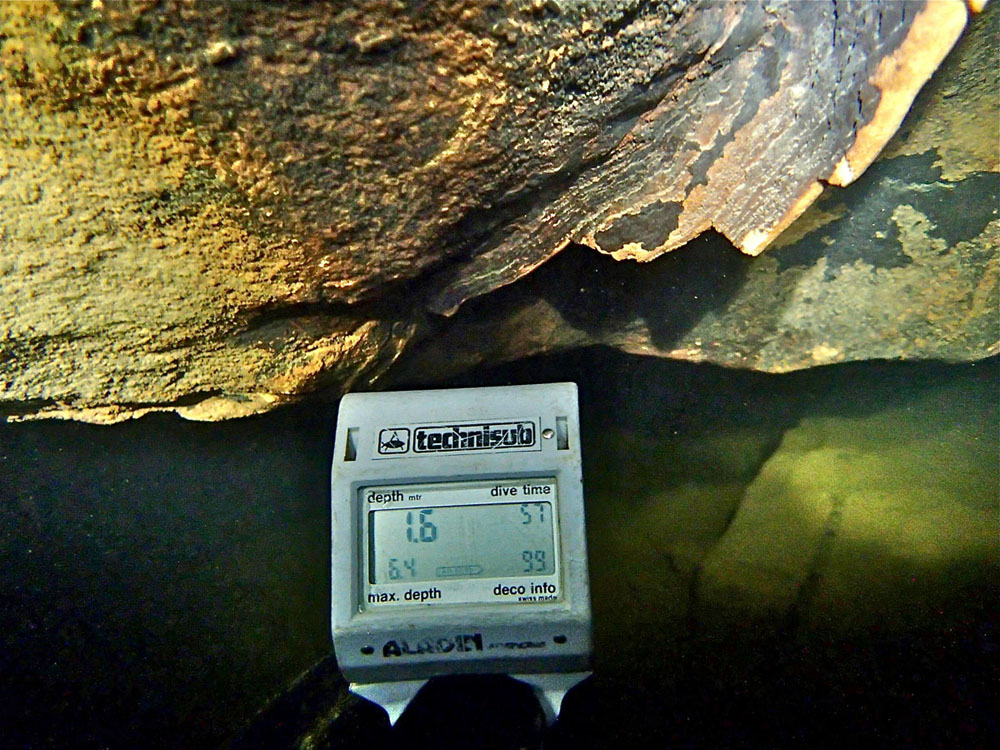

Malham Cove Rising: John Cordingley's survey below shows the extent of present day knowledge and surprisingly it seems to fit in well with Arnold Waterfall's prediction for a major cave at the foot of the cove. Almost a mile of submerged passage have been explored and at the present time John and his colleagues are still pursuing digs at the end of the system. Further details may be found in John's excellent summary of work to date: "CDG Gallery Five: Malham Cove". This may be viewed on the Cave Diving Group website (see Ref below).

A significant question to be answered is whether or not this rising is from a truly 'phreatic' passage or from a 'vadose' passage later flooded by fallen rock and scree damming up the flow of water. There would be vast quantities of glacial meltwaters crashing through the faulted strata discussed above sufficient to form a large vadose streamway, along a line of weakness such as a shale band.

Cordingley's current view is that most of the underwater passages are of phreatic origin:

"* The whole cave formed under phreatic conditions and the whole cave is still phreatic in nature.

* Briefly, before the main Devensian ice advance, a very small proportion of the known passage became vadose (allowing small speleothems to form: see photo below right).

* This small area of the cave would still be vadose today were it not for the later talus accumulation at the foot of the Cove.

* But the whole cave should still be regarded generally as a phreatic system."

In 1996 a concerted effort was made to establish some baselines as to the various routes taken by the underground waters. This work is well summarised in "Malham Area Water Testing May 1996 Dye Tracing Results" (see references). Unfortunately this project, whilst yielding much valuable information, contributed little to the furtherance of cave exploration in the study area. However 'digging fever" was aroused and maybe "Caverns Measureless to Man" will some day be revealed.

References

Tate T, 1879, 'The source of the River Aire'. Proc. Yorks. Geol. Poly. Soc.7, 177-81

Tate T, 1895, 'The Malham Dry River Bed'. Proc. Yorks. Geol. Poly. Soc.13, 58-63.

Howarth J H, 1900, 'The Underground Waters of North West Yorkshire: Part 1 The Source of the River Aire', Proc. Yorks. Geol. Poly. Soc. 14 (1) 1-44

Waterfall A C,1949 'The Malham Moor Sinks'. CPCJ 1.1 4-6

Waterfall A C,1952 'The Malham "Dig'. CPCJ 1.4 197-198

Thomas Hurtley 1786, 'Natural Curiosities of the Environs of Malham-in-Craven'.

Butcher A L 1953, 'When the Frogmen came to Malham Cove'. CPCJ 1.5 photo insert.

Anon 1954. YRCJ 1954 'Cave Explorations - Malham Cove dive'.

Cave Diving Group website may be found at: http://www.cavedivinggroup.org.uk

-

Malham Area Water Testing May 1996 Dye Tracing Results: YSS et al: The Craven Pothole Club Record 50 April 1998 pages 19 to 32.

http://caving-library.org.uk/collections/youtube.php?id=112

Any

shortcomings in the text are entirely my own.

If you would like to get in touch or add information, there is an email

address:

mudinmyhair@btinternet.com

Steve Warren

Website created by WarrenAssociates 2012

Website hosted by Tsohost

Copyright © Steve Warren 2016